Share this Post

What are deepfakes?

Deepfakes are manipulated or synthetically generated images, videos and audio tracks of human faces, bodies, or voices, which look or sound authentic to varying degrees, and are often created using deep learning, a method of machine learning. The result is a subset of synthetic media showing people saying or doing things that they never said or did.

Deepfakes present a new technological development in the long history of media manipulation. Even long before Photoshop, photographs were manipulated with both benign and malign intent, e.g., to create art, but also to produce non-consensual pornography, or for political purposes. Deepfakes, however, augment many of the challenges (and benefits) associated with manipulated audio-visual media for several reasons. Firstly, they are spreading in a changed and challenged information environment, in which the rise of social media and messenger services has eroded the “gatekeeping” function of traditional media and increased the significance of visual information, and in which disinformation is posing an increasing threat. Secondly, most viewers perceive audio-visual media as more credible than text-based media and are less aware of the potential for manipulation. Thirdly, advances in artificial intelligence and computing power have enabled a rapid improvement in the quality and accessibility of compelling deepfakes, making them more common and influential than ever before, while at the same time harder to detect and thus more difficult to regulate.

Deepfakes’ increasing quality and accessibility has led to their proliferation in all areas of digital life, from politics to pornography. Some observers are even convinced that synthetic media will dominate the digital sphere and become the norm for online content in the near future. Depending on their context of use, deepfakes have very different ethical and societal implications, in turn warranting different political and societal responses. Therefore, it is important to understand the current state and potential future of deepfakes’ technological development, the many ways in which various actors employ the technology, and its impact.

Deepfakes: Technological progress and key developers

Deepfakes are based on a variety of artificial intelligence and/or computer graphics techniques. Most deepfakes draw on “Generative Adversarial Networks” (GANs), a specific form of deep learning. In a GAN, two antagonistic neural networks co-create ever-more convincing synthetic media. The first network, the “generator,” creates an output. The second network, the “discriminator,” judges whether the output is fake, feeding the result back to the generator network, which refines its media synthesis.

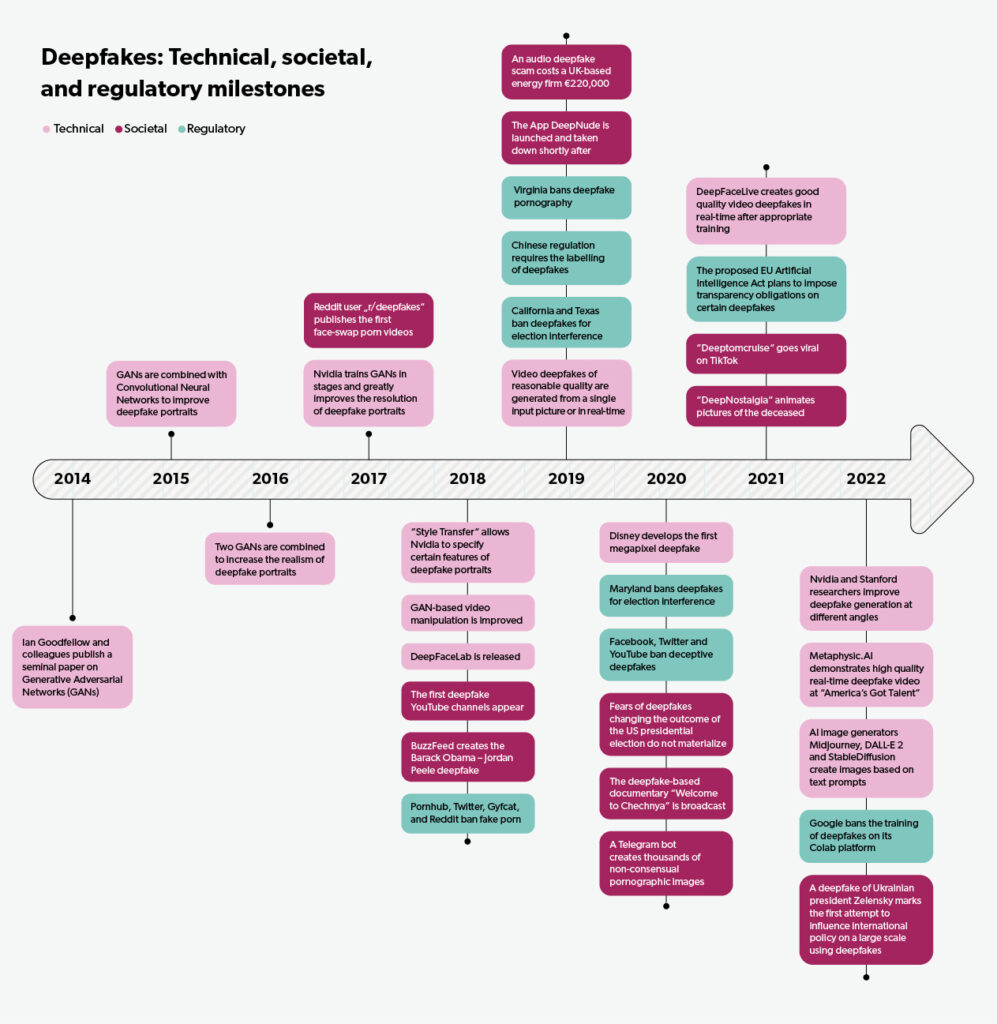

Deepfakes trace their beginning to 2014, when a paper by Google researcher Ian Goodfellow and colleagues laid the technological foundations for GANs. Since then, researchers at universities, start-ups and companies such as NVidia, Samsung and Disney have been working on improving the technology and its results. Concurrent to the development in research and the private sector, in 2017 the technology became available to the public and deepfakes began to proliferate when a user named u/deepfakes uploaded pornographic fake videos to Reddit, in which the faces of porn actors were replaced by those of female celebrities. This user’s profile name led to the term “deepfakes.” This same user also established the first online forum dedicated to creating and sharing (pornographic) deepfakes and improving the underlying technology. Numerous other (code-sharing) fora followed. Technological progress on deepfakes has since been driven not only by scientists and the industry (including a growing number of specialized start-ups), but also by individual developers who often anonymously collaborate on code-sharing platforms such as GitHub.[1]

The technological progress has been immense. While initial deepfake portraits and videos were hard to create and easy for humans to spot, tools are now available online for anybody to create realistic fake portraits with just one click. Synthetic audio is also becoming increasingly convincing, and numerous start-ups have sprung up around this new field. Additionally, a growing number of text-to-speech websites such as FakeYou allow anybody to produce audio deepfakes. Deepfake videos are also a growing realm, and with improvements in open-source code, it is now possible to create fake videos of reasonable quality, with little technological expertise and using a regular computer. In tandem with the improving technology, respective apps and commercial services are expanding, making deepfakes widely accessible. Presently, developers are working on reducing the amount of training material (i.e., audio-visual material of the subject) needed to create convincing video deepfakes (in some cases merely a single input picture). A further unprecedented technological development is the real-time rendering of deepfake videos. In summer 2022, special effects artist Chris Umé demonstrated live on the TV-show America’s Got Talent that it is now possible to produce such high-quality deepfake videos in real time, given sufficient initial images and requisite training of the model.

The speed of deepfake development took most experts by surprise. It is notable that much of this rapid progress has been the result of largely anonymous collaboration: The open-source GitHub page DeepFaceLab lies at the core of some of the most viral deepfake videos and most advanced commercial applications. Thereby, deepfakes are an area where open-source sharing and collaboration manifest as a double-edged sword: They have enabled rapid technological development, but observers criticize that some, e.g., DeepFaceLab remain closely connected to communities and creators of non-consensual deepfake porn.[2] The overarching pattern is that the resources and technological expertise needed to create convincing deepfakes are steadily decreasing, while quality and accessibility are increasing. This trend is set to continue, contributing to deepfakes’ growing popularity.

Sources: Research by the author, the Decoder

Political deepfakes

The public debate about deepfakes revolves mainly around their potential for political manipulation, in particular in the context of elections, such as the fear that deepfakes will compromise candidates or spread incorrect information about election procedures. Such fears were particularly widespread before the 2020 US presidential election, but did not materialize on a large scale. Thus, while deepfakes were used to influence domestic opinion in the US on a smaller scale,[3] as in other (geopolitical) contexts, they have not yet derailed any democratic election. Their increasing quality and accessibility may, however, soon change that. In addition, the fear of deepfake-based manipulation itself poses a threat to democracy to the extent that it shakes public confidence in the integrity of elections and the resulting democratic representation.

More generally, deepfakes undermine people’s trust in shared empirical insights, truths, and facts, obstructing democratic debate and problem solving. They also enable the so-called “liar’s dividend,” a term coined in the context of deepfakes describing how individuals deny incriminating evidence, such as recordings of their speeches or actions, by claiming that the evidence is fake. Since 2020, for example, there has been much speculation in the US regarding the veracity of videos of both Donald Trump and Joe Biden, both by their respective supporters and detractors, showing just how far-reaching the effects of deepfakes have become. Furthermore, less than a month after George Floyd’s murder by a police officer, a Republican politician published a “report” claiming the video of the murder was a deepfake. This example also indicates how the liar’s dividend may further marginalize disadvantaged communities. In repressive regimes, moreover, claims of deepfaked evidence may undermine the work of human rights activists and opponents. As deepfakes spread and the public becomes more aware of them, the liar’s dividend (and deepfakes’ detrimental effect on trust, in general) increases.

Deepfakes can also directly target those whose public expressions make them vulnerable to retribution. This includes members of a political opposition, activists, and critical journalists. A prominent example is that of Rana Ayyub, a Muslim Indian journalist who had reported on a case of rape by a Hindu. A deepfake porn video of her went viral and even led to death threats against her. Deepfake pictures were also used to create a network of fake profiles originating in Russia in 2021, which posted false information about anti-government protests – for example, stating that they were under-attended – to prevent members of the opposition from participating.

Similar networks of false social media accounts with deepfake profile pictures have attempted to exert foreign influence via social media, i.e., to influence the domestic politics of another country.[4] However, none have attracted a substantial following. In 2022, a deepfake of Ukrainian President Zelensky urging Ukrainians to surrender to Russia marked a novel type of attempted deepfake-based interference. It appeared on the website of a Ukrainian TV broadcaster, which had been hacked, and subsequently spread on social media. Although the quality of the deepfake is low, diminishing its impact, this deepfake was historic as it was the first documented attempt to bring about a decisive change of international policy using a deepfake.

Considering deepfakes’ increasing quality, such incidents – and deepfake-based disinformation in general – are likely to increase. As of 2022, however, the grave political threat of deepfakes has not yet materialized. At times, journalists, politicians, and citizens also overestimate deepfakes’ sophistication and scale of use and are quick to report on ostensible political “deepfakes” that later turn out to be less sophisticated – but nonetheless influential – forms of manipulation, so-called “cheap-” or “shallowfakes.”[5]

Deepfake pornography

A 2019 report estimated that 96% of all deepfakes were pornographic, and that 100% of which depicted women. While the phenomenon of deepfakes continues to grow in other areas, this overall disproportion remains. Many open source deepfake projects and fora help users create deepfake porn. Apps like DeepNude circulate on messenger apps such as Telegram and can “undress” the image of any woman. While non-consensual deepfake porn originally focused on female celebrities, its increasing accessibility, along with the reduced amount of training data needed, now allow users to create non-consensual pornographic images of nearly any woman who has uploaded one or more pictures to social media. The result is an abundance of deepfake porn on both regular and designated porn sites, and an increasing use of revenge porn, sextortion, and blackmail.

Creators of deepfake porn often argue that it is protected by the freedom of expression, is entertaining, and does little harm. However, the impact on affected individuals is reportedly grave: Victims feel humiliated, powerless, and intimidated, and often suffer psychological illness and disadvantages in their personal and professional lives. Additionally, deepfake porn harms the sex workers who produced the original content beyond the usual hazards of the industry, since they do not financially benefit from its appropriation for deepfakes (and did not consent to it). Since deepfake porn overwhelmingly victimizes women, it poses a threat to gender equality in a digital society, potentially silencing women and discouraging them from participating in public and professional pursuits. Some observers argue that deepfake porn is a more pressing concern than political deepfakes and that it requires greater attention.

Deepfake crime

Audio and video deepfakes have been used for imposter schemes to defraud both individuals and companies. Infamously, a UK energy firm lost more than $240,000 in 2019 when its CEO was fooled by a synthetic audio posturing as the parent company’s CEO. A second known, similar case concerned a Hong Kong-based bank in 2021. Additionally, fraudsters used an alleged deepfake video of a cryptocurrency executive to obtain $32 million in 2022, and deepfake videos of Elon Musk circulated to persuade people to invest in fake cryptocurrency deals. Deepfakes may one day also be used to sabotage competitors and manipulate stock markets, e.g., by publishing fake videos of CEOs making racist or sexist remarks, or falsely announcing mergers or other large business decisions. Additionally, deepfakes can circumvent facial recognition technology and remote identification procedures. This is suspected to have already occurred, such as when image-manipulation apps were allegedly used by criminals to hack a governmental facial recognition system and conduct large-scale tax fraud in China from 2018 onward. In 2022, the FBI also warned that cybercriminals were using deepfakes to apply for remote IT jobs in companies to gain access to their IT systems. Furthermore, pornographic and other compromising deepfakes can be used for blackmail and (s)extortion, as the case of several (male) Indian politicians shows. Cybercriminals are thus increasingly employing deepfakes, and this trend is likely to continue.

Deepfakes in personal and profitable entertainment, and other commercial pursuits

Deepfakes can also serve new forms of self-expression and participation in digital life. Many YouTube and TikTok channels are dedicated to deepfakes, mainly of celebrities, some of which are very sophisticated.[6] Deepfakes are also used for memes; a growing number of apps also allows users to insert their faces into music or video clips.

The technology also has many commercial applications, particularly in the marketing and film industries: Actors can easily and convincingly be made to look much younger or much older, their lip movements can be adapted in dubbed films, and, in the future, it will be possible to use their original voices for dubbing. Celebrities do not need to travel to the set anymore to appear in films and advertisements. Post-editing can correct misspoken or age-inappropriate words without new footage.

Deepfakes can even digitally “resurrect” deceased actors and musicians for new performances. In the “digital afterlife industry,” deepfakes of the deceased are changing how we mourn and remember: The genealogy website MyHeritage launched DeepNostalgia in 2021, a service animating pictures of deceased relatives. Voice cloning allows people to train an AI model of their voice while still alive, which can interact with their loved ones after their death (as recently demonstrated by Amazon), and it may well become more common for deepfake avatars of the deceased to participate in their own funerals.

In the marketing industry, deepfakes are used to localize marketing campaigns (e.g. to support local shops) or even hyper-personalize them, targeting individual consumers. The fashion industry has also discovered deepfakes, using them to create virtual influencers (virtual humans) and a diverse range of models for online fashion sales. Incorporated into medical assistance technologies, synthetic audio even allows people who cannot speak due to medical conditions to use a digital version of their own voice.

Both non-commercial uses of deepfakes for personal entertainment and digital self-expression and commercial deepfake applications raise ethical concerns, ranging from micro-targeted ads’ potential to deceive and manipulate consumers, to concerns about actors’ futures and their lack of consent to specific deepfakes. Deepfakes of the deceased also touch upon (often unresolved) legal and ethical questions of the depicted individual’s personal rights and dignity, the importance of their consent given while still alive, and deepfakes’ influence on the processing of grief and respective cultural practices in the future.

Deepfakes in education, activism, and satire

Educational deepfakes could allow historical figures to speak directly to students or museumgoers. For example, the Dalí Lives exhibition in St. Petersburg, USA, allows visitors to “interact” with the deceased artist. Other projects (re-)create speeches by historical figures such as former US presidents or the civil rights activist Martin Luther King.[7] Such deepfakes provide new, fascinating, and memorable encounters with history. At the same time, they portray only one (potentially simplified) interpretation of history or a historical figure, and must therefore be employed (and viewed) with caution.

Political activists have used deepfakes of murder victims for campaigns calling for stricter gun laws in the US or intensified criminal investigations in Mexico. Artistic uses alert the public to the dangers of mass data collection, or to critique patriarchal attitudes. The 2020 documentary Welcome to Chechnya pioneered the use of deepfakes to publicize the stories of victims of persecution based on their sexual orientation while protecting their real identities. Deepfakes also figure in political satire, e.g. in a web-show about former US-President Trump, or a TV-show about former Italian prime minister Renzi.

Artistic, activist, and satirical deepfakes often criticize those who wield power, or call attention to socio-political injustices. Here, the deepfake technology allows for the creation of new kinds of intriguing and often haunting content, e.g., by depicting deceased persons, or using deepfakes to allow viewers to empathize with the victims of political persecution by superimposing activists’ faces onto the faces of the prosecuted individuals (for example, instead of blurring the faces or only filming the victims from behind) in the case of the documentary Welcome to Chechnya. However, even deepfakes that are used to promote just causes may deceive viewers, for example, when clips are shared out of context on social media. Furthermore, malicious deepfakes are often labeled as satire to avoid legal prosecution and other countermeasures, including labelling and algorithmic consequences on platforms.

The future of deepfakes

Deepfakes are on the rise. They remain prolific in the context of pornography, but are expanding into every aspect of digital life, including politics, cybercrime, entertainment, advertising, and education. Increasingly sophisticated deepfakes of both celebrities and “ordinary” people will soon become part of everyday digital interactions. Proponents of the “metaverse” even envision a new kind of digital future, in which hyperreal synthetic versions of ourselves – i.e. synthetic clones – interact with each other in an immersive digital world. Thus, deepfakes are expected to enable the creation of much more life-like and realistic avatars for this new digital world.

Deepfakes offer many promises, e.g., for commercial gain, entertainment, and education. They may also enable more meaningful interactions across linguistic and geographic barriers – and even after death, as the digital afterlife industry indicates. Simultaneously, the rise of deepfakes intensifies dangers such as online disinformation, manipulation, fraud, blackmail, and intimidation. It also raises complex ethical and societal questions concerning personality rights, freedom of expression, cultural practices surrounding death and mourning, and more. Scientists, politicians, and societies are beginning to address these questions, discuss desirable ways to deal with deepfakes in different contexts, and take respective action.

Political and societal responses

Regulatory efforts are currently underway in several countries, including the UK and the US, to outlaw non-consensual deepfake pornography and intensify its prosecution. This indicates that politicians, lawmakers and civil society actors are changing their views about the significance of deepfake pornography.[8]

Practically, deepfakes cannot be outlawed categorically, and additionally, this would obviate their many legitimate uses e.g., for education or commerce; moreover, deepfakes (e.g., in politics or entertainment) are protected by the freedom of expression. At the same time, deepfake-based disinformation and hate speech threaten democracy. Decision-makers are thus grappling with ways to deal with such deepfakes on social media. In the European Union, deepfake governance consists of a complex web of self- and co-regulatory activities by social media platforms and increasing regulatory efforts, e.g. via the new Digital Services Act (DSA) and the AI regulation.

Nevertheless, regulation alone will not suffice. Technical advances in deepfake detection are also needed to identify unlabeled deepfakes and to allow society to respond appropriately. Progress on image and audio forensics is ongoing, and approaches focus on a wide range of deepfakes’ traits. However, such progress often facilitates an improvement of deepfakes themselves, making it a “cat-and-mouse-game.” One further, promising development is the growing field of encoding images to obstruct their use for AI-based image synthesis. Systems to verify the authenticity of original and untampered media may provide an additional solution to the challenges caused by deepfakes. However, such systems would have to be prevalent and effective, and they are not insurmountable. Furthermore, they run the risk of further disadvantaging marginalized actors. For example, if content authentication systems become a “watermark” for big media, evidence gathered by citizen journalists and activists recording human rights violations on low-end cellphones whose devices lack such systems will not be considered credible.

Finally, it is imperative to increase citizens’ media literacy and awareness of the threat of deepfakes, in order to reduce the reach of deceptive and other malicious deepfakes. This will help mitigate deepfakes’ negative effects while enabling legitimate and even beneficial uses of the technology.

[1] Recently, computer vision researchers have turned towards new kinds of neural networks, known as “Coordinate-Based Multi-Layer Perceptrons” (CB-MLP), and a specialized form for 3D-scenes, “Neural Radiant Fields” (NeRF). These neural networks – not mainly developed for deepfakes, but used for them – can encode a three-dimensional understanding of a scene and are being used to create increasingly convincing deepfakes from different angles.

[2] Motherboard journalist Emanuel Maiberg argues: “As the DeepFaceLab Github makes clear, if you want to actually learn how to use the software and participate in its improvement, you need to visit Mr. Deepfakes, the home of non-consensual deepfake porn online.”

[3] Two (suspected) deepfakes retweeted by Donald Trump in this context were hardly deceptive (and partially labeled). In addition, a fake intelligence document aimed at compromising Joe Biden was authored by a fake persona with a deepfake profile picture. Of note, it continued to spread e.g., among QAnon reporters even when the author’s fake identity was clarified, suggesting that the deceptive potential of deepfakes is not always decisive.

[4] These include a network that spread a pro-Trump and anti-Chinese Communist Party campaign in 2019, a Chinese network focusing on geopolitical topics in 2020, an allegedly Chinese cross-platform network attempting to prevent US-President Trump’s reelection, a Russian campaign ahead of the 2020 US presidential elections, and a pro-Western network uncovered in 2022.

[5] In 2021, several European politicians held Zoom-conferences with an alleged deepfake of Russian politician Nawalny’s chief of staff Wolkow, which turned out to be the work of two Russian pranksters, one of whom had simply dressed up as Wolkow. In 2022, several mayors of large European cities and EU Commissioner Johansson also held video conferences with an allegedly deepfaked Vitali Klitschko, Mayor of Kiev. Later, it turned out that the same Russian “comedians” had used less sophisticated video manipulation techniques than deepfakes to trick the politicians.

[6] In 2022, DeepTomCruise went viral on TikTok. This series of short clips was created by visual effects artist Chris Umé with the help of a Tom Cruise impersonator and includes some of the most advanced deepfakes to date.

[7] JFK Unsilenced is an audio and video deepfake of former US-President Kennedy delivering the speech that he was to have given on the day of his murder. Similarly, a deepfake shows an altered version of Nixon’s speech, prepared for the eventuality of a failed Apollo-11 moon landing. Deepfakes also power an immersive experience of Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

[8] Victims of non-consensual deepfake pornography often lack legal protection. Usually, the perpetrators remain anonymous, and they are often located abroad. Moreover, the attempt to prosecute producers of deepfake pornography frequently encounters a legal loophole, since the distributed images are synthetic, and the creation thereof is not a criminal offense in many countries.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) and/or its partners.

Share this Post

Does Foreign Electoral Interference Violate International Law?

Interference in democratic decision-making processes carried out by outside powers is anything but a novel phenomenon. Especially during…

Digital Rights in Israel

From Human Rights to Digital Rights The term “digital rights” describes human rights in the digital age. The…

How does the European Union plan on making its food system more sustainable?

Nowadays there is an overwhelming amount of talk about sustainability, which more than ever also applies to our…