Share this Post

The Rise of European Digital Constitutionalism

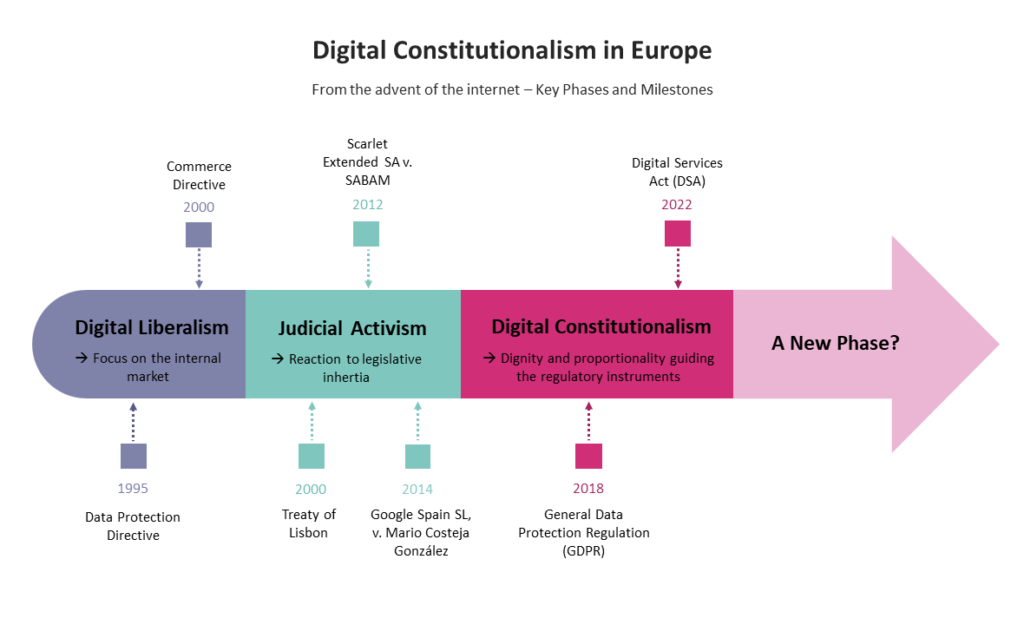

In the last twenty years, the policy of the European Union in the field of digital technologies has shifted from a liberal economic perspective to a democratic approach. This change of heart has resulted primarily from the rise of the information society, and then of the algorithmic society, which has not only created new opportunities, but also posed challenges to fundamental rights and democratic values. One of the most significant changes has been that this technological framework, driven by liberal ideas, has empowered transnational corporations operating in the digital environment to perform quasi-public functions on a global scale.

Until the adoption of the Charter of the Fundamental Rights of the European Union in 2000 and the recognition of its binding effects following the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty, the Union approach was firmly based on this liberal orientation based on economic pillars, namely, the fundamental freedoms such as freedom to provide services. The liberal goal of protecting these freedoms has contributed to influencing the regulation of the digital environment. Both Directive 95/46/EC, known as the Data Protection Directive, and Directive 2000/31/EC, or the e-Commerce Directive, are two examples of the European liberal inclination.

The liberal economic orientation of the Union was challenged by the rampant changes of the digital environment at the beginning of this century. Two major events were among the causes that led to the end of the first (liberal) phase and encouraged the European Court of Justice (ECJ) to assume an active role in paving the way towards a new European constitutional strategy. The first event triggering this phase of judicial activism concerned the rise and consolidation of new private actors in the digital environment; the second involved the recognition of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights (Charter) as a bill of rights of the Union.

Within this new constitutional framework, the ECJ started to apply the Charter as a standard for assessing the validity of and interpreting European legal instruments, thus focusing on the effective protection of fundamental rights and freedoms. Given the lack of any prior legislative review of either the e-Commerce Directive or the Data Protection Directive, judicial activism in the form of the Charter has played a critical role in highlighting the challenges for fundamental rights online, and in so doing, has helped guide the transition from a mere economic perspective to a new constitutional phase, as underlined in Scarlet and Google Spain.

The lesson learned from judicial activism has not gone unnoticed by the Union. The ECJ’s judicial activism has played a crucial role in triggering a new European constitutional phase towards the injection of democratic values into the digital environment. The European Commission demonstrated its awareness of the new digital framework in the years following the adoption of the Treaty of Lisbon. In the framework of the Digital Single Market strategy, the Commission issued a communication underlining the need to ensure that online platforms “protect core values” and increase “transparency and fairness for maintaining user trust and safeguarding innovation.” This is because of the role of online platforms in giving access to information and contents to society and, as a result, their impact on users’ fundamental rights. As the Commission stressed, this role implies “wider responsibility.”

The Consolidation of European Digital Constitutionalism

These early initiatives have given rise to a new wave of soft and hard law instruments whose objectives have been, inter alia, to regulate content and data. This approach is evident in the field of content where new safeguards have been introduced by the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, the amendments to the Audiovisual Media Service Directive, and the Regulation on Terrorist Content. In the field of data, the GDPR has introduced other safeguards and increased accountability to protect the fundamental rights of data subjects. Furthermore, the Commission has introduced soft-law regulatory solutions through which it is trying to cooperate with platforms in the fight against certain forms of expression, for instance, disinformation.

These measures have anticipated the adoption of the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act whose aim is to provide a new legal framework for competition and digital services while also mitigating the constitutional challenges raised by online platforms and protecting European democratic values. Particularly, the Digital Services Act will provide a horizontal system of substantive and procedural safeguards that limit platforms’ power in content moderation.

The Digital Services Act is just one piece of a broader European strategy reviewing the objectives of the Digital Single Market, in particular consisting of the Communication “Shaping Europe’s Digital Future,” the Communication “A European Strategy for Data” and the “White Paper on Artificial Intelligence.” The proposal for a regulation on artificial intelligence technologies is another example of this European reactive framework.

Within this framework, European digital constitutionalism should not be considered as a mere constitutional reaction. Rather, it is a long-term, proactive strategy to protect democratic values in the algorithmic society from being eroded by unaccountable powers.

The Paths of European Digital Constitutionalism

The European sensitivity to challenges posed by the rapid digitization of society results from the European constitutional roots, which are based on horizontal and protective dimensions of rights. This approach underlines a constitutional approach of the EU to the exercise of powers that with the onset of the digital age are no longer only public, but rather, are increasingly the domain of private actors. This new constitutionally oriented phase triggered by the reaction of the Union to the emergence of private powers underlines the relevance of dignity and proportionality as primary European constitutional guidance limiting liberal approaches that could end up undermining democratic values.

The path of digital constitutionalism is not unique. Regulating digital technologies reflects different values. While China is pursuing a model of technological developments oriented towards surveillance and public control and the US liberal approach leads tech giants to dominate digital markets, and continue to extend their power to new sectors according to their business logic, the European approach reflects a strategy that primarily focuses on the protection of fundamental rights and democratic values.

However, the design of digital policy is not only a matter of values but also governance. Even if illiberal regimes have tended to exercise greater control of the Internet relative to the liberal democracies, transnational private actors are also an enormous force, as they have consolidated delegated and autonomous realms of power that establish their values on a global scale, thus creating a de facto para-constitutional framework competing with the rule of law.

The transnational dimension of these challenges also influences the scope of this framework, thus leading to tensions between extraterritoriality and protectionism of digital policies. The European Union has already shown its ability to influence global dynamics, and scholars have referred to this attitude as the “Brussels effect.” The Union is increasingly aware of its ability to extend its regulatory soft power: influencing the policy of other areas of the world in the field of digital technologies. It is also making headway in developing its narrative about digital sovereignty.

This framework underlines how digital constitutionalism provides multiple angles to analyze the exercise of powers in the digital age. Digital constitutionalism is not only about mapping bills of rights or underlining the interferences raised by public powers. It is also a broader call for enlarging the debate about how rights and freedoms are mediated as a result of power relocation in the digital age.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) and/or its partners.

Share this Post

"In dealing with disinformation, many different things need to come together"

Disinfo Talks is an interview series with experts from around the world, who tackle the challenge of disinformation through…

How is Artificial Intelligence (AI) changing the workplace?

Algorithm management in the workplace Artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming an integral part of the ordinary workplace. Various…

What is Germany's strategy in the race for a quantum computer?

Quantum computing promises a significant leap in computing power for mathematical problems in the development of medicines, logistics,…