Examining the reach of the EU's Digital Services Act: How will it affect non-EU jurisdictions?

Share this Post

When online users in Tel Aviv, Mexico City, Delhi today go to their preferred global news website, they are likely to receive a request to approve the collection of personal data, rather than have such information collected by default. This relatively new data protection mechanism has little to do with regulations in these users’ jurisdictions. Rather, it is a result of the EU’s GDPR, whose overhaul of data-collection and online privacy practices has benefitted not only European consumers, but consumers worldwide.

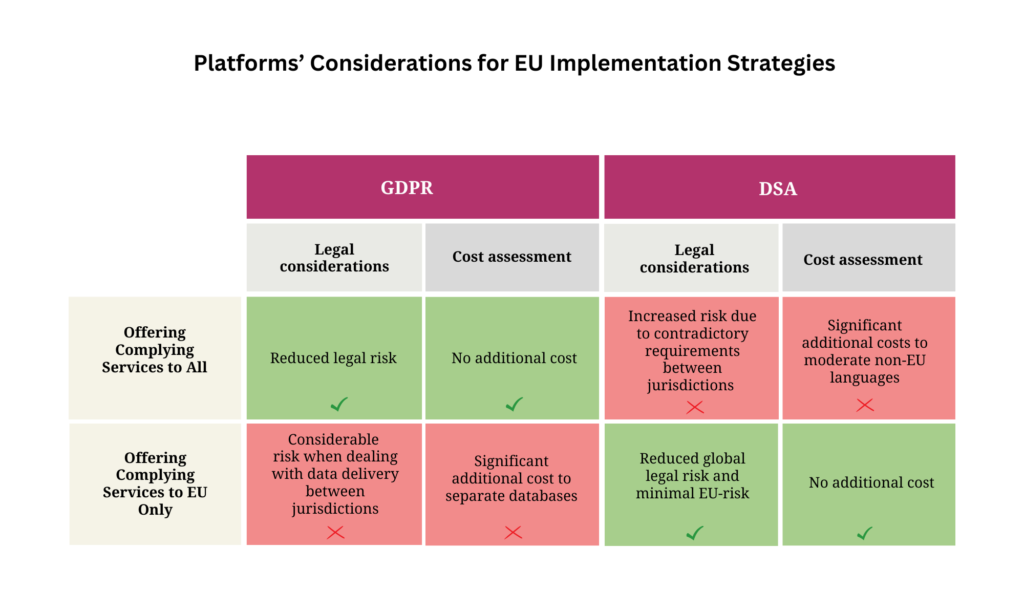

The GDPR’s cross-jurisdictional impact does not stem from the word of the law, but from business interests. In preparation for the regulation’s enactment in 2018, when businesses had to decide whether to apply GDPR rules globally or cherry-pick European users and provide them with enhanced data protections, they by and large determined that the former option was to their benefit since it reduced implementation costs and legal risk.

With the passing into law of the new Digital Services Act (DSA), the question arises as to whether platforms will adopt DSA regulations globally as they did the GDPR, leading to de-facto enactment of the DSA across jurisdictions. Stated otherwise, will users outside the EU benefit from the DSA as much as they did from the GDPR? Answering this question requires a review of the various rules within the DSA and how they intersect with the platforms’ interests. This endeavor, as will be seen, reveals a nuanced outcome: While non-EU users might ultimately enjoy some of the DSA’s benefits, this will be limited, since the platforms, in contrast to their response to the GDPR, are expected to attempt to minimize cross-jurisdictional spillover as much as possible.

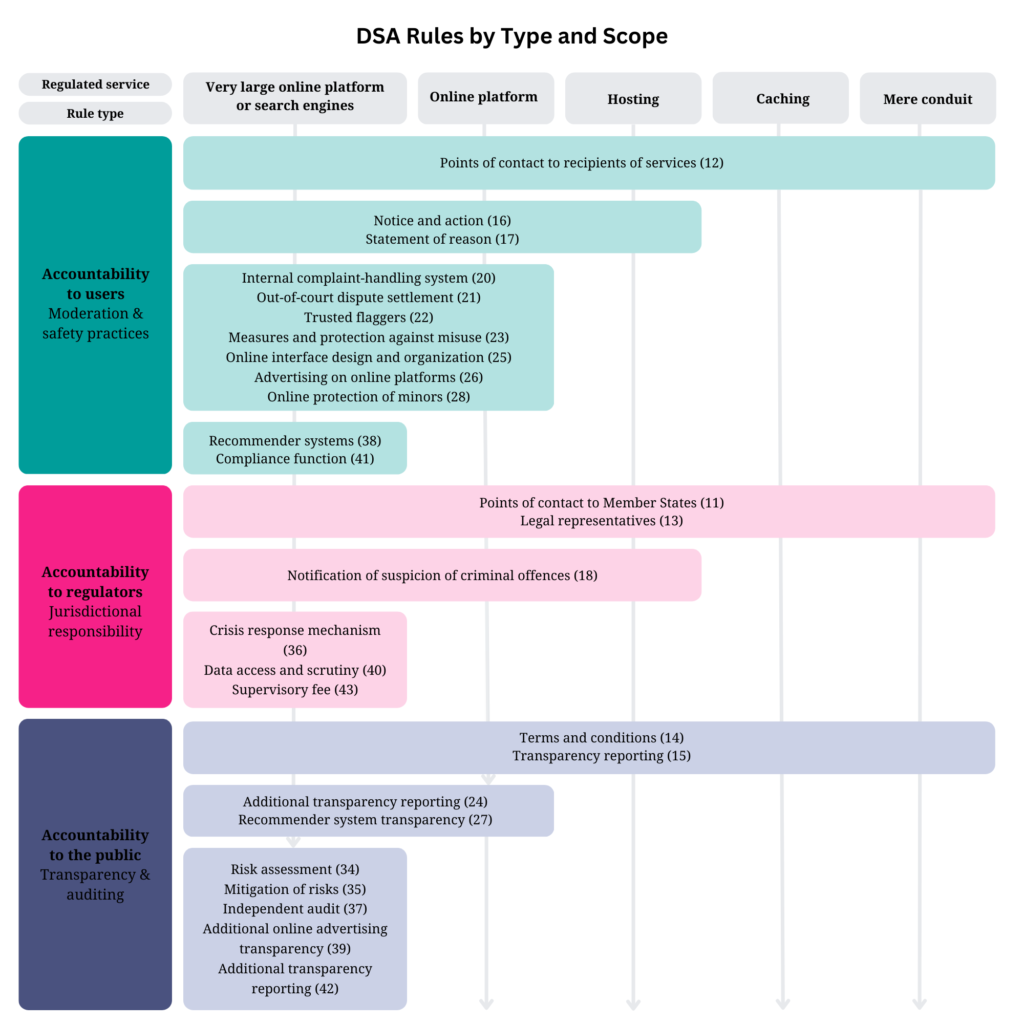

Three Modes of Accountability

At its core, the DSA enhances three modes of platform accountability. The first is accountability to users, expanded through rules that govern moderation and safety practices. These are the practices through which platforms define, identify, and remove problematic content uploaded by users, such as hate speech and medical disinformation. DSA Article 12, “Points of Contact to Recipients of Services,” which stipulates the range of customer support services required for in-scope platforms to provide users with, specifically defines best practices when conducting these operations and requires platforms to provide users with as much information as possible in the event of subjecting them to content removal.

The second mode of accountability is to EU and Member State regulators through rules that detail the nature of the legal presence required of platforms in each and every Member State. These include an explicit requirement to submit points of contact to authorities (Article 11) and to notify law enforcement of any suspected criminal offense involving a threat to safety (Article 18). Very large platforms (VLOPs), as defined by the DSA, are also required to prepare mechanisms and protocols to cooperate with the EU Commission when an extraordinary crisis, such as a terror attack streamed live online, requires immediate platform response (Article 36).

Lastly, the DSA establishes platform accountability to the public at large for societal, non-user specific, harms that might occur, from increased anxiety and body dysmorphia among teens, to electoral conspiracy theories leading to violence and political unrest. To increase platform accountability to the public, the DSA relies on third-party audits, transparency reporting, and due diligence. For example, Article 24 requires platforms to publish annual transparency reports, which include data on the effectiveness of their content moderation practices. This requirement is intended to help the public determine whether platforms are doing enough to mitigate the societal risks of their products.

DSA Rules by Type and Scope (article number in parenthesis)

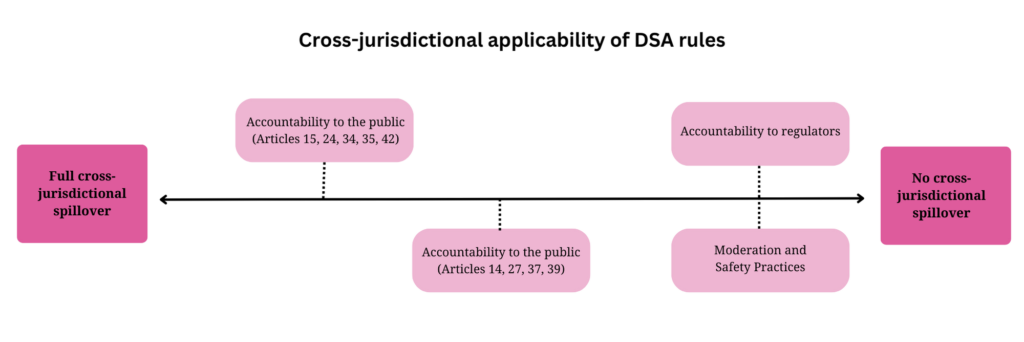

Accountability to non-EU regulators – no cross-jurisdictional spillover

When examining these three modes of accountability, the second, accountability towards jurisdictional regulators, stands out as the mode that will not have any cross-jurisdictional spillover. No private entity is likely to willfully increase its obligations towards a state regulator in the absence of a stipulated requirement. Conversely, spillover of the other two modes depends on whether platforms can and have an interest in expanding their impact beyond the EU.

Accountability to non-EU users – No cross-jurisdictional spillover

The area of greatest discretion for platforms under the DSA is in whether to apply cross-jurisdictional spillover in the moderation and safety rules. As was the case with the GDPR, platforms have full range in deciding whether to offer uniform services to all users or to invest in creating two separate moderation operations – a DSA-compliant operation servicing EU citizens and non-compliant operation servicing all other users. The two operations would differ in various ways including, for example, having different “community standards” and offering EU users more extensive customer support services.

Based on past actions it is safe to assume that in contrast to the GDPR, platforms will choose to create separate moderation operations. Most significantly, that was their decision when implementing a German moderation regulation from 2018, the NetzDG Act. Two primary considerations can explain this approach. The first is the very practical prospect of contradictory legal requirements in different jurisdictions.

One such example is the case of Article 17 of the DSA, which requires that when a company moderates content, it must provide a “statement of reasons” to the users, detailing what steps were taken and why. As part of this requirement, platforms must inform a user if the reason behind a given inquiry is notice by a third party (including local law enforcement). However, concurrently, a 2021 law in India prohibits platforms from notifying users when their content was removed due to a request by Indian law enforcement. To conform to the demands of both EU and Indian law, platforms will necessarily have to separate their moderation operations based on geographical location. Therefore, confining the scope of their DSA-complying operations to EU citizens only makes sense, and is consistent with an already expanding practice of differentiating moderation services based on geographical location.

The second consideration behind limiting DSA moderation rules is reducing compliance costs. Content moderation is a resource-intensive practice. It requires using complex automated systems that identify problematic content, training and maintaining sufficient human manpower that makes final decisions on content removal, and establishing clear platform policies that adapt platforms’ “community standards” to the evolving nature of online harms. All these efforts are location-specific, and, more importantly, language-specific. An English-speaking moderator’s ability to correctly examine content in Hebrew, for example, is extremely limited. An automated machine trained with English content would not do much better. As a result, for platforms to implement the DSA outside of the EU, they would need to invest additional resources in ramping up their non-EU-language moderation operations without legal obligation to do so, making it more expensive than separating operations. This is exactly the opposite conclusion from the implementation cost assessment for the GDPR, where it was found to be cheaper to enforce rules globally rather than to separate EU and non-EU customers on platform databases.

Accountability to the non-EU public – Limited cross-jurisdictional spillover

In contrast to the situation for individual non-EU users, there is a silver lining for the non-EU public. With the implementation of the DSA, the overall ability to scrutinize online platforms will increase everywhere. Many aspects of this mode of DSA accountability, therefore, will spill over by default beyond EU borders, regardless of platforms’ interests.

For example, the services that online platforms, especially social media platforms, offer to EU and non-EU customers are virtually the same. Therefore, if a company conducts a risk assessment for its EU services, a DSA-required process in which platforms predict what societal harms might arise from their operations, it effectively conducts this assessment and consequent mitigation measures for its global services. Similarly, when a platform publishes a transparency report on its moderation tools used in Europe, regulators, academics, and civil society outside of the EU can better understand what tools are used, or can be used, in their jurisdiction.

Admittedly, these rules are likely to have a limited impact on the non-EU public since they will lack an intentional consideration of local markets’ unique threats. For example, in some South Asian markets, WhatsApp has become a main source of news for the local population. This is not the case in the EU, and thus there are unique societal threats posed by WhatsApp in South Asian markets that would not surface through risk assessments conducted for the use of WhatsApp in European markets. And some of the DSA’s public-facing accountability rules might have less impact than others. For example, the requirement of readable terms and conditions, stipulated in Article 14 of the DSA, will likely have no benefit to those who do not speak one of the EU Member State languages, since platforms will not translate these documents into other languages. Still, the value of this increased transparency on platforms’ global services cannot be overstated. Such information can be used to better inform the public on how to deal with platform mistakes, scrutinize their attempts to safeguard user safety, and inform local lawmakers when drafting local regulations in the future. This is the most significant development the DSA offers to the non-EU public.

Overall, analyzing the three modes of accountability offered by the DSA suggests that while online platforms are global in nature, regulation of their safety and moderation practices will forever be a jurisdictional task. Those who rely on EU regulators to provide users across the globe with the protections they need will encounter limited, incremental progress at best. For faster results, and for rules to consider the unique challenges of local markets, it is up to local lawmakers to envision, legislate, and enforce local rules.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) and/or its partners.

Share this Post

The Case for an Emergency Regime for Cyberspace

It’s a scenario that’s been on the very top of every cybersecurity official’s list of nightmares for a…

Privacy by Design and Competitive Advantage: a Whatsapp Exodus?

Authors: Eduardo Magrani and Lucas van Hattem The start of the new year might not have taken the turn WhatsApp was hoping…

"Policymakers need to empower people to make good decisions online"

Disinfo Talks is an interview series with experts that tackle the challenge of disinformation through different prisms. Our talks…